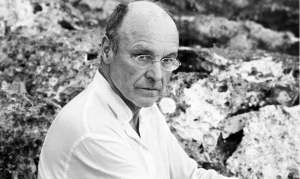

Anselm Kiefer

Artist Bio

Born at the close of World War II, Anselm Kiefer reflects on and critiques the myths and chauvinism that propelled the German Third Reich to power. With Wagnerian scale and ambition, his paintings depict the ambivalence of his generation toward the grandiose impulse of German nationalism and its impact on history. Balancing the dual purposes of powerful imagery and critical analysis, Kiefer’s work is considered part of the neo-expressionist return to representation and personal reflection that came to define the 1980s. At that time, Kiefer was the centerpiece of a critical debate on the continued validity of painting, the ability of representation to heal deep historical wounds, and the legacy of fascism.

Zweistromland: The High Priestess, 1985–87, depicts the union of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers as an intersection of rusted, crumbling modern train tracks, bridges, or superhighways. Water often signifies life, hope, and renewal, but Kiefer’s reinterpretation suggests thwarted ambition and broken promises. With hues of blue and shadowy passages of black and brown, the monumental painting offers a dour look at Germany’s past—a country believed by its Nazi ancestors to be a new, modern cradle civilization on the scale of Mesopotamia and subsequently revealed to be a deeply flawed force for hate.

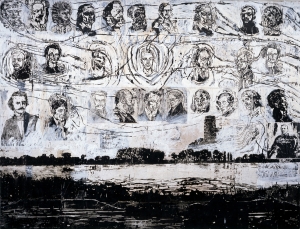

In Deutschlands Geisteshelden, 1973, Kiefer superimposes historical meaning on a setting of personal significance, his former studio in a rural schoolhouse. Painted on six strips of burlap sewn together, Kiefer creates a textured, wooden room receding sharply into space. The work recalls both hunting lodge and a memorial hall. Fires burn on the walls, and the surface suggests that the entire scene has been singed with flame. According to art historian Mark Rosenthal, this work demonstrates that “Kiefer’s attitude about a Germany whose spiritual heroes are in fact transitory and whose deeply felt ideals are vulnerable is not only ambivalent but also sharply biting and ironical....These great figures and their achievements are reduced to just names, recorded not in a marble edifice but in the attic of a rural schoolhouse.”

![Anselm Kiefer - Alarichs Grab [translation: Alaric's Grave], 1969-89](/sites/default/files/styles/artis_bio_page-300px_scale/public/art/kiefer_alarichs_grab.jpg?itok=vybit_aq)