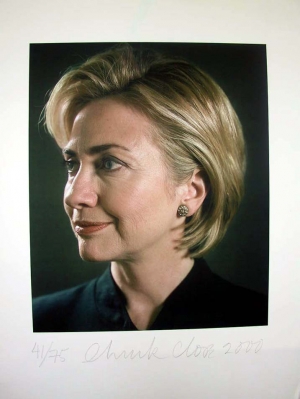

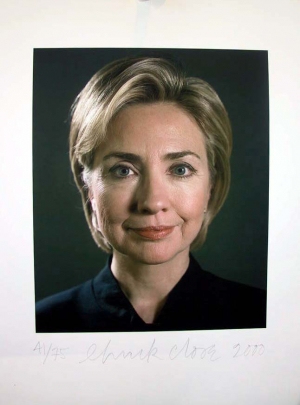

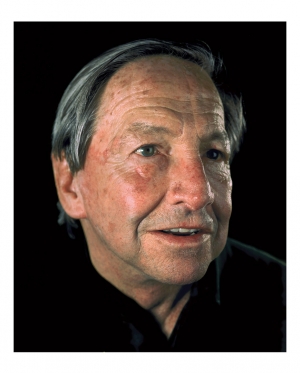

Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Chuck Close

Artist Bio

Chuck Close’s paintings are studies in both patience and the limits of seeing. When his monumental close-ups of human faces appeared in the late 1960s, there was already a burgeoning return to realism in painting, even if the dominant modes of art making at the time were color field painting, pop art, and minimalism. In this return to realism, the photograph was often used as a guide to enhance the detail of painting or, as in the case of Gerhard Richter, to question the reliability of both painting and photography. Close took a fresh and different approach, using an airbrush and a grid to painstakingly expand a photographic image to monumental size. In the process, Close showed the limitations of the photograph through his intuitive adaptation and changing of the image to accommodate the demands of painterly detail and scale.

Early paintings such as John, 1971–72, are often described as Photorealist. Indeed, Close refers to photographs to create his artwork, employing their inconsistencies of perspective as much as their verisimilitude. The painting began with a source photograph of Close’s friend John Roy, a painter that he had met at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 1964. In John, the sharp detail of the rim of the subject’s glasses contrasts with the blurred, soft focus of his shoulders and the back of his hair, as it likely did in the original photograph. But instead of using mechanical means to transfer his images onto canvas, Close works entirely from sight to achieve the intensely animate detail of his early paintings, sectioning off the reference photographs into grids and transferring them by hand, square by square, onto his monumentally sized canvases.

April, 1990–91, was completed after Close had experienced a horrendous arterial collapse in 1988, which left him partially paralyzed. Using essentially the same process as with John, Close painted this work by holding a brush in his mouth. The scattering of colors produces beautiful passages of abstraction that lock into a realistic visage from a distance. In this work, Close found a way not only to overcome his paralysis but also to expand his mediation on painting and photography.