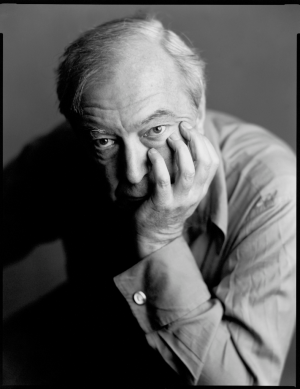

Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Jasper Johns

Artist Bio

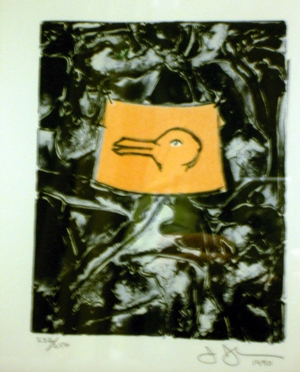

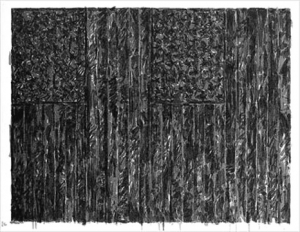

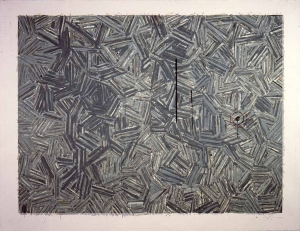

Jasper Johns’s groundbreaking 1958 installation at the Leo Castelli Gallery of his famous target and flag works changed the current of New York painting and had an extraordinary impact on contemporary art. In the paintings, Johns presents images that move into the realm of objects and wrestle with the validity of representation as a philosophical concept. The targets and flags, in the words of critic Leo Steinberg, were “co-extensive” with their canvases, existing somewhere between a symbol and a thing in the world. Not only did these paintings begin Johns’s successful dismantling of modern art through his ironic analysis of structures and rituals, but they also became the innovative new ground on which a generation of painters and sculptors made their work. Johns’s own career spans from the flags, through the device motif in the early 1960s, into the crosshatch paintings of the 1970s, and to his complex, densely layered recent works.

Watchman was made while Jasper Johns was living abroad in Tokyo, Japan, in 1964. The seminal work features a wax cast of Johns’s friend’s leg, two canvas panels, and half of a standard dining table chair. The surface of the painting is seemingly in the midst of action. The words “red,” “yellow,” and “blue” printed partially on left side of the canvas appear as though in a state of erasure, while their colorful pigment counterparts appear (also disrupted) on the right. The ejection of the chair upward to the sky leaves an aftermath of orange, green, and gray, like a falling rain of expressive marks across a once ordered surface. Overall, Watchman is a painting that is trying to be more than a painting; it is caught in the very moment where the world of thought and representation (of symbols and signs) is transitioning into the world of action and physical expression.

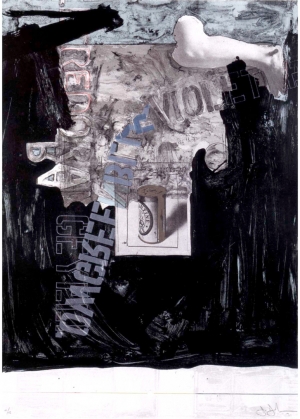

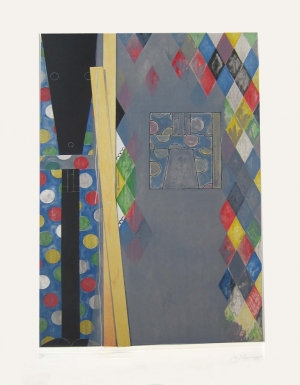

Johns repeats and collects motifs throughout his career, ready to use them at anytime for different purposes and ends. For example, though Watchman might be seen as a further critique of modernist painting, Johns’s later work takes on more mysterious and elusive ambitions, engaging both the history of painting and more personal concerns. Untitled, 1992–94, for instance, collects Johns’s familiar early methods such as the use of flagstone imagery and text and positions them alongside the remembered plans of Johns’s childhood home, a cruciform image containing a young boy and Icarus, and the outline of a soldier depicted in Northern Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece.