Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Robert Rauschenberg

Artist Bio

Robert Rauschenberg, along with Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly, broke the stylistic and conceptual dominance of abstract expressionism in the 1950s and expanded the horizons of art. Rauschenberg is perhaps best known for two bodies of work, his Combines of the 1950s and his silkscreen paintings, which he began in the early 1960s. These works preceded and helped inspire pop art as well as an increased blurring and retooling of the various media of the visual arts. Rauschenberg has also been a great ambassador for the visual arts, both as a famous collaborator in John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s dance compositions and as an international teacher with the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange (R.O.C.I.), an organization that in the 1980s brought art projects and new art-making technologies to foreign countries.

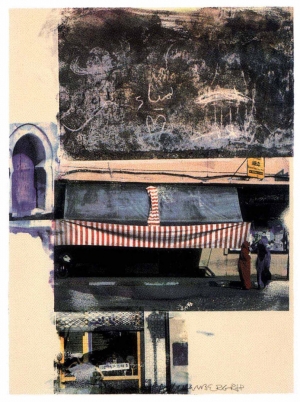

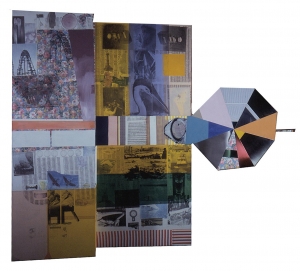

Rauschenberg’s Combines are a hybrid between painting and sculpture. In these works, Rauschenberg mixes items found in alleys, on the streets, or in junk stores with paint and other materials of art making. Partially because of his use of such ordinary items, Rauschenberg has become known as an artist who, in his own words, “works in the gap between art and life.” An early manifestation of this mode and a key work in his career is Untitled, 1954. A collage of wood, newspaper, comics, sundry clothes, and old lace, Untitled is saturated with a thick sealing coat of paint. The surface is open to drips and chance combinations, not with an expressive intent as in abstract expressionism but instead with a field of unexpected juxtapositions and perceptual shifts.

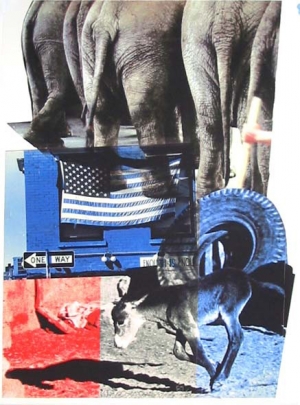

Untitled, 1963, denotes Rauschenberg’s gradual shift to silkscreen painting in the early 1960s. The various images of John F. Kennedy, weather balloons, instruments, and plates, as in the Combines, create a field of association not unlike the deluge of information found in a newspaper or on television. The viewer’s eye revolves around the canvas, picking up symbols and visual clues, enacting a day-to-day perception not provided by the rigorous painting composition but by the often random collection of objects and images that one encounters just walking down the street. The introduction of this way of seeing into fine art is one of Rauschenberg’s most important contributions, loosening long-held traditions of painting.