Sherrie Levine

Artist Bio

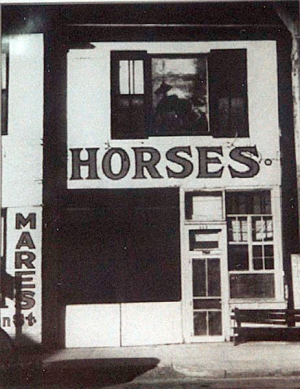

Sherrie Levine reinvents famous images and objects by removing (or appropriating) them from their original contexts and placing them into new, meaningful positions. During the early 1980s, Levine followed a theoretical framework of art making led by the rise of post-structuralist criticism as well as historical reassessments of surrealism and Marcel Duchamp. The crux of the criticism focused on originality and the strategy of appropriation. In her works Untitled (after Walker Evans: negative) #8, 1989, and Untitled (after Walker Evans: negative) #9, 1989, Levine rephotographs well-known Walker Evans images. Explaining her project, Levine said, “I hope that in my photographs of photographs an uneasy peace will be made between my attraction to the ideals these pictures exemplify and my desire to have no ideals or fetters whatsoever.” By removing herself from the original artwork through conceptual distance, Levine creates a new theory, a new situation for understanding.

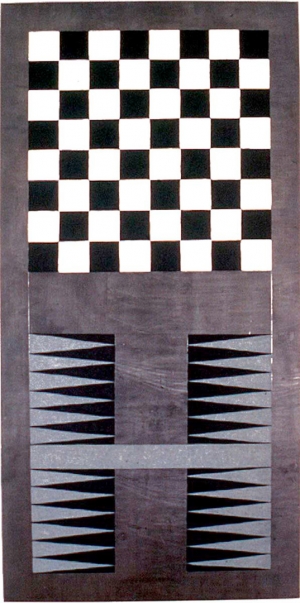

Double Checks #6, 1988, features the famous chessboard image pervasive in Dadaist work. In this piece, Levine both references the notions of strategy and gaming and the mass reproduction of images. For Levine, art making can be likened to chess, a set of preset rules reproduced infinitely through the situations and minds brought to it. Toward the end of the 1980s, Levine’s focus turned to what were historically considered low art forms such as comics. Untitled (Mr. Austridge: 1), 1989, takes a character from George Herriman’s Krazy Kat cartoon and reproduces it in a straightforward, unembellished way in casein on wood. As with the chessboards and photographs of photographs, the image is rearranged and resituated, moving the popular cartoon into the hermetic avenues of conceptualism.

Untitled (The Bachelors: “Larbin”), 1989, is a reinterpretation of Duchamp’s famous The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, 1915–23. The original Duchamp piece presents a bachelor machine set in relationship to a hovering bride image at the top of a glass surface. The work is an allegory of erotic relationships, which Levine sees as an interpretation of the Biblical story of Susanna and the Elders, where two men attempt to blackmail Susanna into sexual intercourse. In order to destroy the power of the male suitors working together for sexual deception, Levine separates each bachelor from the machine, isolating them in separate vitrines. Using the relationship to Duchamp’s work, Levine sets a series of reflections into motion, including originality and sexual desire, changing the power structure presented in both Duchamp’s piece and the original story.