Yayoi Kusama

Artist Bio

In 1961, Yayoi Kusama, then thirty-two years old, displayed a painting that was thirty-three feet long and almost ten feet high at Stephen Radich Gallery in New York. The painting, no longer extant, was one of the largest of the abstract expressionist era, a time in art known for expansive canvases and large-scale pursuits. Kusama’s work, however, was made exclusively with small marks, her gestures as tiny as the canvas was enormous: little arcs of white pigment applied with a brush accumulating by the thousands, giving the field a dense web of touches seemingly uncountable in their multitude. To stand in front of this work would have been to stand in a complete environment, to sense a vastness. Kusama has used this technique into the present. Her “Infinity Nets,” as these paintings came to be called, are performances in paint, obsessions in space, and literally other worlds made visible.

Kusama paints what she sees, as a still-life painter would paint a bowl of fruit. From an early age, she was prone to hallucinations due to mental illness, vivid experiences of the world distorted and enhanced by colors and shapes. “These forms come not only from the artist’s observation of nature, but from an inner mindscape,” critic Bob Nickas writes, “the paintings can be seen as representations of space, as well as images of what cannot easily be represented—infinity or hallucination.” Kusama’s work resides somewhere between representation and abstraction: for the artist, representation, and for everyone else, abstraction.

Throughout the 1960s and early 70s, Kusama’s paintings and performances mirrored an age where vision was constantly challenged and new vistas consistently sought. At various points, Kusama was espoused by artists across a variety of formats and theoretical concerns, including pop, minimalism, and surrealism. Perhaps more pointedly, her work appealed to New York’s turbulent political and social environment. Kusama staged multiple fully nude happenings across the city to protest the war in Vietnam, economic disparity and the excesses of Wall Street, and the hierarchy and gender inequality of museums. At the same time, her visions matched the transcendental aspirations of psychedelic drugs and mind-altering spiritual movements of hippie culture.

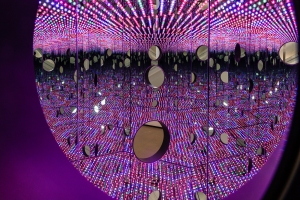

Ultimately, it was in installation where Kusama found a way to best express the impact of her interior mind on her external environment. “As I was painting, absorbed,” Kusama told Index magazine in 1998,” I realized that the new was spilling over the desk....I was painting on the floor. And then, one day, when I woke up, I found a red net covering a window....The entire room was covered with red net.” Kusama’s nets became inhabitable environments. Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, 2013, is just such an inhabitable Kusama world. A room is completely covered with mirrors and dozens of LED lights hang from the ceiling. As the multitude of lights reflect, they accumulate and expand exponentially. This sense of infinity has been with Kusama from the beginning, always looking for clearer ways to express itself. Inside Infinity Mirrored Room—The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, Kusama’s world is the viewer’s world.