Pastorale

About This Artwork

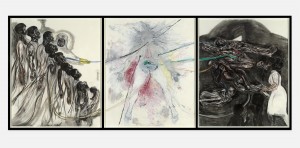

The title of Kara Walker’s Pastorale is deeply ironic. It invokes rural farmland, a serene setting for much poetry, painting, and literature. Yet the drawing depicts a riotous 1920s cityscape that includes a woman wearing a cloche hat, a radio caught in the midst of destruction, and an early Mickey Mouse character without his iconic ears. On the brick wall is a pair of minstrel eyes, as if the wall is surveilling the mayhem. Slavery is written into America’s pastoral vision of itself, into nineteenth-century perceptions of southern rural life, and into the legacy of that past. In Pastorale, Walker shows the price of that horrible vision. The figures portrayed are, presumably, the descendants of the same formerly enslaved Black Americans who migrated out of forced labor on plantations and into cities, where today they continue to experience a persistent, systemic lack of freedom and justice.